|

|||||||

•CSI President Morales Gets Pay Raise, CSI Students May Pay More

•CUNY Chancellor Raises SAT Math Admission Scores to CSI & CUNY

•Look Who USED To Teach at CSI!

•Mayor Bloomberg’s Budget Cuts CUNY

•CUNY Trustee Randy Mastro Dropped

> POLITICAL DISCOURSE

•Comrade X: The Fourth Estate & Revolution

•What's the #1 cause of global warming?

> POETRY

> CULTURAL DISCOURSE

•A Weeknight Out on the Town for Booze & Brains

> ART & PHOTOGRAPHY

•Look Who USED To Teach at CSI!

•What's the #1 cause of global warming?

> DEPARTMENTS

| Join our e-mail list for announcements! |

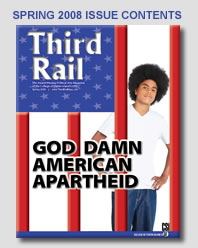

COVER STORY

AMERICAN APARTHEID

FDR’s Plan For Segregating America

and its Lasting Effects

In the 1960 essay, “the origin of the work of art,” the German philosopher Martin Heidegger suggests, “what seems natural to us is probably just something familiar in a long tradition that has forgotten the unfamiliar source from which it arose.”1

Heidegger’s quote is an apt description concerning the residential segregation that is evident in cities across the United States. Many view our residential housing patterns as a “natural” result of the “free market” rather than the consequence of government intervention. Yet through an historical examination it becomes evident that government, and not the so-called “free market,” was the primary impetus in constructing the post-WWII modern housing market. As a direct result government intervention greatly exacerbated African American segregation and created a discourse that denied its own impact by emphasizing the “free market” as the primary causal agent. This process had dire social consequences for many African Americans who were socially, economically, and politically isolated from the rest of society.

GOVERNMENT INTERVENTION IN HOUSING

In 1933, in the throes of the Great Depression, a thousand foreclosure procedures were initiated daily as the housing market was collapsing.2 To help alleviate the housing crisis, the FDR administration created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) in June of 1933. HOLC provided “long-term, self-amortizing mortgage[s] with uniform payments spread over the whole life of the debt.”3 This new practice was counter to the prevailing historical wisdom that people should completely pay off their homes soon after purchasing them. It was not until the 1920s that even short-term five to ten year mortgages became popular. These mortgage plans were often renewed for seven more years, “...but if a mortgage expired at a time when money was tight, it might be impossible for the homeowner to secure a renewal, and foreclosure would ensue.”4 HOLC completely transformed the structure of the housing market and enabled homebuyers greater security in their purchase. In an effort to assist those who had lost their homes due to foreclosures, the HOLC provided loans to buy back their property.5

The HOLC mushroomed into an enormous bureaucratic network of investigators, whose primary duty was to determine the worth and feasibility of individual homes and the overall neighborhoods in which they resided. The HOLC investigator’s appraisal techniques relied on a census style questionnaire that mixed personal demographic information with data about the condition of the housing stock in a given neighborhood. This was not new in appraisal systems; the originality “...lay in the creation of formal and uniformed system of appraisal, reduced to writing, structured in defined procedure, and implemented by individuals only after intense training.”6 The appraisers’ written statements were not made in objective isolation, but rather in a larger cultural paradigm or discourse that induced racial prejudges which influenced their decision-making. As a result, “redlining” was implemented on a massive scale and received government sanction.7

The HOLC codified a complex number, letter, and color coded system that rated neighborhoods based on socioeconomic criteria. This criteria was then utilized in real estate appraisal decisions based on the desirability of providing loans. White, wealthy “racially” homogenous neighborhoods received the highest rating on the four scale rating system. Jewish neighborhoods, even affluent ones, were never able to receive the highest rating. Black areas were deemed undesirable and consequently were given the lowest rating. HOLC applied information from their databases and created color-coded “Residential Security Maps” which were utilized in their offices all over the United States.8 These maps provided HOLC appraisers with detailed information on where Blacks currently resided and where they may be encroaching on white enclaves. Even a small minority of African Americans in an overwhelming Caucasian neighborhood would cause HOLC appraisers to designate the area with a low rating, and thus would be an impediment to its residents securing high-quality loans.9

Although the HOLC favored neighborhoods that were white and wealthy, its real damage was in systematizing and universalizing a racist discourse in the housing market. HOLC’s well-crafted racialized maps were adopted by private lenders and subsequent governmental housing programs that heavily utilized “redlining” techniques as part of their modus operandi.10 This is not to claim that racial and ethnic discrimination did not exist in the housing market prior to government intervention, but only to argue that it created a uniformed standard supported by the most influential financial and regulatory entity in the United States at the time—the federal government. Prior to governmental intervention, racial and ethnic discrimination in housing was propagated at the localized level, and “anti-racial agitation was checked by the prevailing spirit of public policy and no ready liaison could be effected between federal officialdom and bigotry.”11

HOLC’s racist classification techniques had its most powerful influence on a subsequent New Deal program that adopted these methods and expanded them enormously: Columbia historian, Kenneth T. Jackson, noted (in 1985), “no agency of the United States government has had a more pervasive and powerful impact on the American people over the past half-century than the Federal Housing Administration (FHA).”12 The program’s genesis was inscribed in the National Housing Act of 1934. The FHA worked in conjunction with the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (GI Bill), which was initiated by the Veterans Administration (VA).13 The FHA provided mortgages for prospective homeowners through commercial lending agencies. The lending institutions provided mortgage loans on a massive scale without the risk of losing money in the case of default, because the FHA completely insured the loans. This program created a major transformation in the housing market. Down payments for homes went from the lowest rate of 30% to only 10%, and were completely amortized with long-term lower monthly payment plans and interest rates. The effect reduced foreclosures “from 250,000 non-farm units in 1932 to only 18,000 in 1951,” and generated a national house-building boom that created more homeowners and new suburban developments than ever before: “between 1934 and 1969 the percentage of families living in owner-occupied dwellings increased from 44% to 63%.”14 Yet the FHA had an inverse effect on the development of urban inner cities, by greatly exacerbating, what in the vernacular is termed “white flight.”

The FHA favored new all-white suburban developments over older racially mixed urban housing stock, thus it became less expensive for white families to move out to the suburbs than live in urban localities. The FHA Underwriting Manual explicitly restricted real estate developers “from introducing ‘incompatible’ racial groups into white residential enclaves.”15 The Manual emphasized racial and class homogeneity as a way of maintaining a stable housing market in a given venue. It further advised residents to create “covenants, which were legal provisions written into property deeds,” to exclude African Americans from purchasing property.16 The FHA produced even more elaborate maps than did the HOLC. These sophisticated maps pinpointed where blacks currently lived and predicted future movement into white areas: “In a March 1939 map of Brooklyn, for example, the presence of a single, non-white family on any block was sufficient to mark that entire block black.”17 The racial separation policies promoted by the FHA were so strict that an apartheid fence had to be constructed between a black neighborhood and a white area before mortgages would be approved in the Eight Mile road section of Detroit (made famous in the Eminem film, 8 Mile).18 The FHA’s policies concretely cemented homogenous neighborhoods across the country where class, race, or cultural differences were viewed as a threat to real estate value. At the same time, the policies destroyed many urban heterogeneous neighborhoods where different groups lived side by side, or at least in close proximity to each other. From 1935 to 1952 “less than 1 percent of new dwelling construction was for the nonwhite families who comprise[d] 10 percent of the population.”19 In cities that were composed of a large African American presence, the FHA often provided no assistance. Harvard scholars, Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton illustrate the ramifications of this policy:

[As late as 1966] . . . the FHA had no mortgages in either Paterson or Camden, New Jersey, both older cities where the non-Hispanic white population was declining during the 1950s . . . Given the importance of the FHA in the residential housing market, such blanket redlining sent strong signals to private lending institutions, which followed suit and avoided making loans within the affected areas. The lack of loan capital flowing into minority areas made it impossible for owners to sell their homes, leading to steep declines in property values and a pattern of disrepair, deterioration, vacancy, and abandonment.20

This encouraged remaining whites to vacate urban areas for suburbia and take their capital with them, leaving blacks with little resources. In fact, by 1970 whites represented a small minority in both Paterson and Camden.

The people who were in the most need of assistance in securing a long-term low interest mortgage, the poor and working-class minorities, were excluded in favor of white middle-class citizens who received the bulk of $119 billion the FHA spent insuring homes between 1934 to 1974. Close to 50% of suburban homes in the United States from 1950 to 1970 received federal government assistants in acquiring a good mortgage, and as a direct result, by the late 1960s, the majority of white American families owned their own home.21 What had been the exclusive privilege of the wealthy, had become the norm in white American society, due to huge government expenditures that disproportionately benefited them. In 1955, in the aftermath of WWII, Columbia urban planner Charles Abrams described FHA policies:

FHA adopted a racial policy that could well have been culled from the Nuremberg laws. From its inception FHA set itself up as the protector of the all-white neighborhood. It sent its agents into the field to keep Negroes and other minorities from buying homes in white neighborhoods. It exerted pressure against builders who dared to build for minorities, and against lenders willing to lend mortgages . . . It not only insisted on social and racial ‘homogeneity’ in all of its projects as the price of insurance but became the vanguard of white supremacy and racial purity—in the North as well as the South.22

PROPAGANDIZING A GOVERNMENTAL MYTH

The government housing programs assisted Caucasians in believing that the racial spatialization patterns in suburban and urban areas were not a product of government intervention, but rather a “natural” development of the “free market.” Historian David M.P. Freund claims that most historians also downplayed the impact of FHA programs in fostering racial apartheid and transforming the housing market. These historians make two points: Firstly, they argue that racial discrimination existed in the housing market prior to governmental intervention; and, secondly, they admit that the government greatly expanded and improved mortgages, but that mortgages did exist before government involvement and are an inherent part of the “free market.” In contradistinction, Freund points out that housing economists view FHA programs as having completely transformed housing policies in the United States vis-à-vis financing and racial discrimination. These housing economists argue that the market was not responsible for the long-term amortized mortgage with low interest rates, but rather it was the government’s policies that resulted in these conditions. Freund notes that the “consensus” belief of housing economists is that the housing market would be completely unrecognizable if government intervention had never taken place23: “...the state did not merely revive and expand existing housing markets—or awaken ‘hibernating’ capital, as many contemporaries liked to say—but rather was instrumental in creating new supply, new demand, and new wealth.”24 One could argue that the government invented the modern housing market, and in so doing, transformed the way millions of Americans lived for the better, or, in the case of poor blacks, for the worse.

Racial discrimination had also previously existed in the private housing market, but it was not an institutional, universally unified policy until the government, through the HOLC and FHA programs, forced private lenders to adopt a system of racial segregation.25 Initially, in the early 1920s, the largest lobbying organization for real estate interests, the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB), promoted a strong anti-racist agenda in housing.26 Of course, the membership of the NAREBA had conflicting viewpoints. For instance, in 1923 a high-ranking NAREB official produced a document that argued that people of certain races might lower the home value in a given community; this was not NAREB’s official policy, but rather one member’s view outlined within a discourse of opposing views.27 But by 1927, NAREB publications openly promoted the idea that whites and blacks had the right to exclude each other from buying their property. NAREB official documents did not explicitly target blacks as a primary cause of home depreciation until 1943,28

four years after the FHA codified this belief in their Underwriting Manual. After 1943, with the government’s backing, NAREB produced manuscripts, college courses, and trained brokers that promoted the idea of racial segregation as good real estate policy.29 Racist ads created by real estate companies proliferated in mainstream culture: “builders began to advertise the ‘absolutely restricted’ neighborhood (no Negroes, Jews, or other minorities), and ‘reasonably restricted’ neighborhoods (Jews, etc., but no Negroes).”30 The FHA promoted and legitimized a totalizing racist discourse surrounding the issue of housing by invoking the “free market.”

The FHA propagated a narrative based on the myth that the “free market” was the primary deciding factor in housing sales, home financing, and residential living patterns in the United States. This narrative pushed forward the premise that government only slightly assisted the “free market” in these activities. Simultaneously, the government narrative disseminated the belief that racial segregation was based on well-founded scientific economic principles, and not on racism per se; the market, not racist human beings determined these polices. The New Dealers promoted market forces as the creative energy in the new housing market because they had to phrase their programs in an appealing fashion to make it politically digestible to the “free market” proponents in Congress and private industry.31

The FHA sponsored a huge marketing campaign utilizing radio, film, newspapers, fliers, conventions, and live speakers to promote their programs cloaked in “free market” rhetoric to a largely white audience. During the first week of the campaign, the FHA sent close to 30,000 lending agency documents outlining its procedures, and spent around $200 million in its first four months. Over half of the country’s daily newspapers provided sections, sometimes totaling over 30 pages, detailing the “free market” housing programs the FHA offered.32 In 1941, an official for FHA, Abner Ferguson, spoke to black business leaders and crystallized the propaganda his agency promoted in claiming that the FHA does not discriminate, but by law cannot interfere with the “free market” in deciding what types of residents are desirable.33 As Freund points out, “on the issues of homeownership, neighborhood integrity, and race, federal programs helped popularize the story that suburban growth and prosperity, as well as racial segregation and poverty that accompanied it, owed nothing to the state’s own efforts.”34

The FHA propagandized a racist discourse that permeated throughout society from media representations to formal FHA conventions to a simple conversation with a neighbor over a white picket fence. This created what Michel Foucault referred to as a “normalizing” discourse which promoted and legitimated racist attitudes: “suburban residents, realtors, and elected officials defended racial restrictions by pointing to the racial compatibility guidelines from FHA appraisal manuals. Private sector publications continued those guidelines—if in a more muted form—well into the 1960s,”35 and the FHA “continued to encourage the use of privately published appraisal standards that identified racially ‘mixed’ occupancy as an actuarial risk.”36 This message had such an impact that even today white suburbanites often justify racial exclusion in their neighborhoods by stating that property values would decline. This discourse provided Caucasians with an ontological justification for segregation and an accompanying myth of how they succeeded in the “free market” at much higher rates than minority groups.

PUBLIC HOUSING: A PROGRAM OF APARTHEID

In the absence of mortgages that were long-term, self-amortizing, and with structured uniformed low interest payment plans, the poor, largely black, urban residents in the United States were provided public housing. Kenneth Jackson delineates the effects of public housing:

The result, if not the intent, of the public housing programs of the United States was to segregate the races, to concentrate the disadvantaged in inner cities, and to reinforce the image of suburbia as a place of refuge from the problems of race, crime and poverty. By every measure, the Housing Act of 1937 was an important stimulus to deconcentration.37

The 1937 Housing Act (Wagner-Steagall Act) created the United States Housing Authority (USHA), which provided funds to local municipalities to set up housing agencies responsible for the constructing, maintenance, and management of public housing projects. The USHA deposited long-term loans and subsidization to local governments for initial building costs. These large developments provided jobs for an underemployed construction workforce, but as soon as the post-War recovery was in full swing, the USHA was badly under funded.38

Due to a Federal Court ruling in 1935 that prohibited the government from exercising eminent domain in creating land for public housing, every individual community had the right to refuse public housing funds. This exacerbated segregation: white middle-class communities often refused the government’s funding, thus keeping their municipalities project free and often minority free too. As a consequence of these actions, projects were usually built in poor, socially and economically isolated sections of urban America (ghettos). This process resulted in dichotomous images in many citizen’s minds: suburbs are safe, white havens from societal ills; while inner cities are black, dangerous places filled with “social pathologies.”39

CONSEQUENCES OF APARTHEID

The social and economic isolation of the projects often resulted in depressing and dangerous living conditions for its occupants and for those residents within the adjacent neighborhoods. Although these conditions were not an accident, but rather the cause of racist social policies, nonetheless, many in the middle-class blamed the poor residents. A common, but completely erroneous belief, propagated by the federal government, was that white middle-class people succeeded on their own accord without the assistance of government, so why can’t these poor residents achieve the same success? Kenneth Jackson makes it clear that the effect, if not always the intent, of housing policy in the United States greatly enhanced the opportunities for one group and greatly diminished the life chances for another group:

American housing policy was not only devoid of social objectives, but instead helped establish the basis for social inequities. Uncle Sam was not impartial, but instead contributed to the general disbenefit of the cities and to the general prosperity of the suburbs.40

Because of government policies the cities became largely black and poor, while the suburbs were affluent and white. As opposed to being checked and restricted by the federal government, racial discrimination in housing was actually promoted by the government. This gave racists like the Levitt brothers the ability to create enormous apartheid housing developments where no African Americans resided: “In 1960 not a single one of the Long Island Levittown’s 82,000 residents was black.”41

Segregation implemented from the federal government had a wide-effect: it set a tone of racially exclusive tactics as acceptable governmental policy that was mimicked at the local level across the country. Suburbanites often utilized covenants, zoning ordinances, and FHA backed polices to deny poor urban residents the opportunity to move into their neighborhoods, while at the same time, accepting no responsibility for the array of problems in the inner city. For example, city zoning laws were utilized as a tactic by local governments to keep out certain undesirables from living in suburban neighborhoods: “apartments, factories, and ‘blight,’ euphemisms for blacks and people of limited means, were rigidly excluded.”42 This also meant that heavy industry was often placed in urban localities, and the effect of these environmentally racist zoning laws can be seen in the high rates of asthma among inner-city children. Another consequence is the inequitable nature of school funding in the United States; the local tax base often determines the amount of funding a school district receives. Thus, a system was created where inferior educational opportunities are the norm in poor urban areas, resulting in significantly lower life chances for these pupils. This had a dramatic effect in stabilizing the status quo: the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu suggests education replicates and reproduces the class structures.

One reason most citizens do not make a connection between governmental policies and the array of problems that exist in the inner cities is the lack of an historical analysis. To speak of historical relationships and complexities as a cause of the social position of many poor African Americans today is often considered taboo. The historical relationships have been diffused, left without much of a trace. Rather, talk of social dysfunction is mired in patronizing discourses of self-responsibility (Bill Cosby), or the resurgence of eugenics (The Bell Curve). This relegates most of the responsibility to those who have been the victims of historical government sanctioned oppression. The same government used its power of hegemony to propagate an ahistorical discourse of the “free market” as the primary cause of segregation in housing patterns. Yet an historical examination yields us knowledge of the unfamiliar source from which those circumstances we consider natural and familiar arose.

FOOTNOTES:

1. Krell, David Farrell, ed. Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings From Being in Time to The Task of Thinking. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1993, pg. 150.

2. Jackson, Kenneth T. Crab Grass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford, 1985, pg. 193.

3. Ibid., pg.196.

4. Ibid., pg. 197.

5. Massey, Douglas S, and Nancy A. Denton. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993, pg. 51.

6. Jackson, Op. Cit. pg. 197.

7. Ibid., pg. 197.

8. Ibid., pg. 199.

9. Ibid., pg. 201.

10. Massey and Denton, Op. Cit. pg. 52.

11. Abrams, Charles. Forbidden Neighbors: A study of Prejudice in Housing. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1955, pg. 151.

12. Jackson. Op. Cit. pg. 203.

13. Ibid., pg. 203.

14. Ibid., pg. 204; and Massey and Denton, Op. Cit. pg. 53.

15. Freund, David M.P. “Marketing the Free Market: State Intervention and the Politics of Prosperity in Metropolitan America.” In The New Suburban History, edited by Kevin M. Kruse and Thomas J. Sugrue, University of Chicago Press, 2006.

16. Jackson. Op. Cit. pg. 208.

17. Ibid., pg. 209.

18. Ibid

19. Abrams. Op. Cit. pg. 172.

20. Massey and Denton. Op. Cit. pg. 55.

21. Jackson. Op. Cit. pg. 215.

22. Abrams. Op. Cit. pg. 229-230.

23. Freund. OP. Cit. pg. 18.

24. Ibid., pg. 20.

25. Ibid., pg. 18-19.

26. Abrams. Op. Cit. pg. 154.

27. Ibid., pg. 155.

28. Ibid., pg. 156.

29. Ibid., pg. 157.

30. Ibid., pg. 171.

31. Freund Op. Cit. pg. 21-23.

32. Ibid., pg. 24.

33. Ibid., pg. 30.

34. Ibid., pg. 32.

35. Ibid., pg. 29.

36. Ibid., pg. 31.

37. Jackson. Op Cit. pg. 219.

38. Ibid., pg. 224.

39. Ibid., pg. 227.

40. Ibid., pg. 230.

41. Ibid., pg. 241.

42. Ibid., pg. 242.